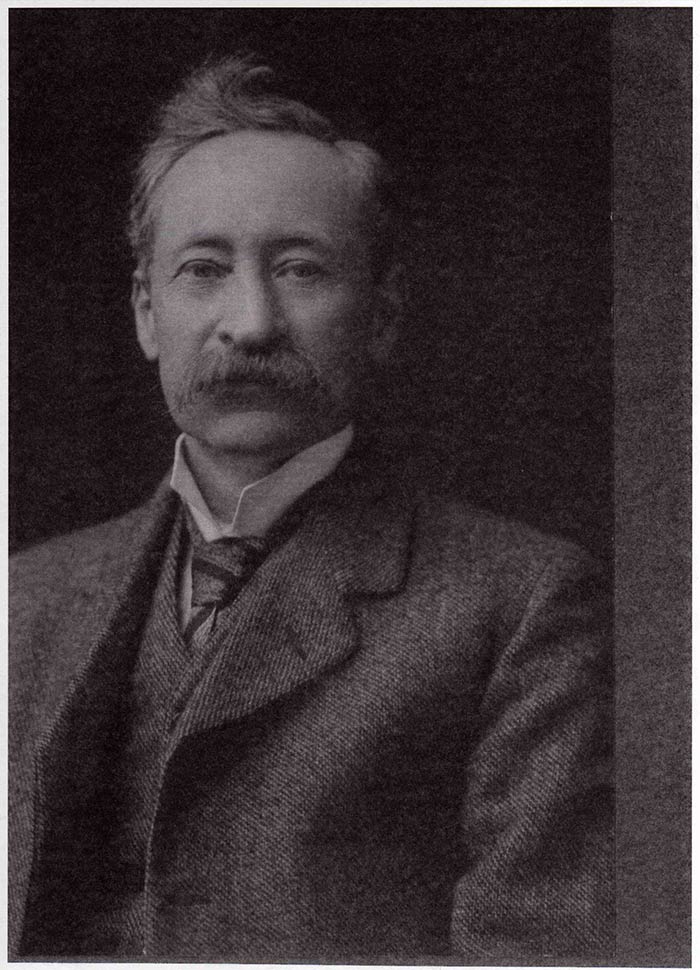

Eden Phillpotts as dramatist

Eden Phillpotts was born in India in 1862 and brought up in Plymouth. In 1879 the family moved to Ealing. In his youth in London he studied acting after hours while working as a clerk in an insurance firm, but had to abandon hope of becoming a professional actor because he could not control his legs (Dayananda, 1984, 10). In 1899 he moved back to Devon, living first at Torquay than at Broadclyst. Though he never lived on Dartmoor, in his early years he used to walk the area extensively to research his Dartmoor cycle of novels. He is now remembered principally as a Dartmoor novelist, but he wrote thirty-five plays for the stage, some of them very successful. The best known is The Farmer’s Wife (Phillpotts, 1917), an adaptation of part of his comic novel Widecombe Fair, which ran for 1,329 straight performances at The Court Theatre in London between 1924-7, but Devonshire Cream (Phillpotts 1930) and Yellow Sands (Phillpotts and Phillpotts, 1926), the latter written with his daughter, were also popular in their time.

Phillpotts’s plays were essentially aimed at the London stage, where he began his theatrical life, though some of them were first performed at theatres in other major cities such as Manchester and Birmingham. In this respect nothing had changed since the days of John Ford – there had been no tradition of performing plays on Dartmoor since the days when the Church authorities in Ashburton and Chagford had funded Mystery and Hood plays. The Farmer’s Wife (1916) and Devonshire Cream (1930) present rural life on Dartmoor as the urban audience of early twentieth century London might have wished to think of it: quaint, comic, and faintly exotic. The following extract from The Farmer’s Wife is a good example:

SWEETLAND. I do puzzle the people a bit! I’m that nice in my speech and use fine words. (Very pleased with himself, leaning towards her.)

LOUISA. No -‘tis your funny voice, I believe. (Laughs.)

SWEETLAND (sits bolt upright in his chair; the smile fades away). My “funny voice”! You wouldn’t hurt my feelings, Louisa? LOUISA. Hurt your feelings, Sweetland! Not likely. Why should I?

SWEETLAND (offended). I don’t want my voice to sound funny on your ears-far from it.

LOUISA.(frankly). I’m sorry. I’d sooner pleasure you than most men, and I think you know it. (Takes gloves off.)

SWEETLAND. Then don’t you interrupt. We lovers are kittlecattle and must have a loose rein, or there’s trouble. I’m like a raging torrent, you may say; and yet there’s that in me that won’t take “yes” for granted. ‘Tis a native modesty, Louisa. LOUISA. Marrying again! We all knew you would. I am glad. I wish you joy of her, whoever She is. But what’s that got to do with breaking into King’s Head!

SWEETLAND (brightly, again quite pleased with himself). Good Lord, Louisa, you’re very near as humble and backward as I am myself.

LOUISA. The fat hen you want – was it for the wedding breakfast?

SWEETLAND. No – for supper. (Laughs.) I was talking in parables, my dear. I wasn’t only coming to tell you I’m in love. I was going to name the party. (She begins to understand what’s coming.) I’ve cast my eyes round Little Silver and brought ‘em to rest at King’s Head. (She is getting up. He rises and restrains her movement to rise. Sits again.) I’ve chosen you to sit at my right hand, Louisa. I don’t say it in no rash and proud spirit. I’m a man that a little child can lead, but a regiment of soldiers couldn’t drive. You’re properly fortunate, and so am I – so am I. We’ve both been married before and both drew a prize. But there’s no call to rake up the dust of the dead.

LOUISA. No, don’t do that. (She again moves to get up)

SWEETLAND (rises- in movement to restrain her, standing above her chair). You bide quiet till I’ve finished, then you can have your say. (Crosses and stands L. of chair, back to fireplace. She is then on his R., but quite clear of him from all parts of the house.) There’s a good bit of poetry bid in me, and you bring it out something wonderful. Only three nights agone I said to my Petronell, as I looked across the valley – I said, “There’s Widow Windeatt’s lights a-glimmering up there to King’s Head, and here’s our lights glimmering down here to Applegarth. Be blessed if us ain’t twinkling out for each other,” I said, “like a couple of glow-worms in a hedge.” Pretty good poetry – eh.”1

Nevertheless Phillpotts was the first significant Dartmoor writer of fiction to write consciously ‘Dartmoor’ work, and The Secret Woman (1913), adapted from one of his most serious and tragic novels, can be called the first consciously ‘Dartmoor’ play, asserting through its setting, its dialect and its outlook that it is not just a play written by someone who happened to live in the area, but a play about Dartmoor. Thomas Hardy had already made rural regional subject-matter fashionable – he had forced it into the arena of serious consideration by casting it, during an era when classical literature held sway among intellectuals, in the mould of classical tragedy. Something of this influence found its way into Phillpotts’ work: traces of the outlook of the Ancient Greek dramatists are discernible in his novels, which are generally tragic in tone. The Secret Woman is in such a vein, though there is far less evidence of the influence of Greek tragedy in the play than in the novel, partly because of the nature of English Edwardian drama – essentially drawing-room and naturalistic, in the school of Ibsen. The Secret Woman was first produced by Granville Barker at the Kingsway Theatre, London, in 1912 amid a storm of controversy. The Lord Chamberlain, in his role as Censor, had refused to grant the play a license, demanding that two sentences should be taken out. This Phillpotts, as a matter of principle, refused to do. A letter supporting his stand, signed by many of the leading authors of the day including Conrad, Galsworthy, Conan Doyle, Shaw, Wells and Bennett, appeared in The Times. In the end permission was granted to give six morning performances without charge to the public (Dayananda, 1984,p 11). Like Ford’s major works, The Secret Woman deals with forbidden love. Married farmer Anthony Redvers has a secret affair with a much younger woman, Salome Westway, for whom his son Jesse has an unrequited passion. Phillpotts had an incestuous relationship with his daughter Adelaide (the co-author of Yellow Sands) 2, which makes a curious co-incidental link with the Elizabethan playwright from Ilsington whose most famous play ’Tis Pity She’s Whore is a study of incest. Phillpotts’ relationship was abusive, beginning when his daughter was a child, and ending with him refusing to speak to Adelaide after she got married.Such a discovery revealed after his death casts a dark shadow over his work. What can be usefully stated in comparing him with Ford is that both share an interest in love which is frowned on by society, and this also links Ford and Phillpotts with the next literary figure in the history of Dartmoor theatre, John Galsworthy.

1 Extract from The Farmer’s Wife (Phillpotts,1917).

2 For a full discussion of this, see Dayananda, James Y. Ed. Eden Phillpotts (1862-1960) Selected Letters, pp 213-250. Lanham: University Press of America, 1984.

Mark Beeson